Review

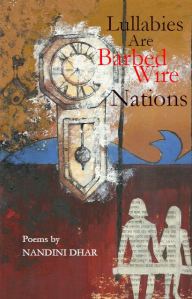

Lullabies Are Barbed Wire Nations by Nandini Dhar

Two of Cups Press, 2015

Reviewed by Nettie Farris

Lullabies Are Barbed Wire Nations, by Nandini Dhar (Two of Cups Press, 2015), is a collection of twenty-one narrative prose poems in the fabulist tradition. The setting is Bengal, India 1975-1985, an “obsolete and brimming nation,” “a free and brimming nation.” These poems trace a map, not of a nation (built on mud, silt, clay), but of the relationships between women. In contrast to the relationships between men and woman, which are grounded in the body, the relationships between females (in this collection) are grounded in the psyche, in dream, and in folklore.

The protagonists in this magical story are twins, who “arrived, freed of the burdens of history”: Tombur and Toi. “Two parts of the same word” (Bengali for full to the brim). The poems are in the voice of Toi, who begins her narrative before she was born: “Long before we became twins and sisters we were dolls—carved in our mother’s noonday dreams.” At times, Tombur seems almost an alter ego, the strong female who makes her own demands, physically fights back, the female Toi might wish to be, though she purports that she “[wants] to be a river. Not a river and a body combined. Just a river.” In contrast, the women she is surrounded by are “rivers and bodies combined.”

Burdens are domestic rather than political; “home sweet home” is not so sweet: “Milk boiling over the tap dribbling on mold-ridden brick the children breaking their bones the doves flapping their wings and someone somewhere from in between the walls slurped on tea.” The twins strike the word “bride” from their vocabulary: “Girls who became brides disappeared. And those who didn’t came back from their husbands’ homes as jackfruit trees.” Grandmothers (who ride around the house on a skillet—like Rumpelstiltskin on a spoon) are conflated with the “juju-lady,” a figure from folklore imported from Africa, a figure whose job is to “scare errant children who [refuse] to take afternoon naps,” although she seems much more sinister, or at least the grandmothers do.

These are poems that can be read again and again, with always something new to discover. Yet the reader shall never get the entire story mapped. As Toi says of Tombur toward the end of the book, “These map-like patterns she drew and re-drew. But she was not moving any closer.”

Nettie Farris lives in Floyds Knobs, Indiana and is the author of Communion (Accents Publishing, 2013). In 2011 she received the Kudzu Poetry Prize. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her collection Fat Crayons appeared in September 2015 from Finishing Line Press.